HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The Great Chinese Famine

The Great Chinese Famine began in late 1958 and lasted until early 1962. The death toll is difficult to ascertain and has become a topic of historical debate. Estimates range from 10 million to as high as 55 million, with the consensus of most historians falling somewhere in the middle.

Likewise, the causes and outcomes of the famine are subject to considerable debate. Though ostensibly caused by drought and weather conditions, the Great Famine was exponentially worsened by communist policies and meddling with traditional agricultural methods and ecosystems. Both were unfurled during Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward.

This disaster would have political ramifications for the Chinese Revolution. It exposed the Great Leap Forward as a failure and led to criticism of Mao Zedong, opening up divisions within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It also led to the temporary sidelining of Mao, who resigned the chairmanship of the People’s Republic in April 1959, though he retained his position at the head of the CCP.

According to official line of the government and the CCP, the Great Famine was caused by a string of natural disasters. Communist historiography refers to it not as the Great Famine but the ‘Three Years of Natural Disasters’.

There are seeds of truth in this claim. In mid 1959, the Yellow River (or Huang Ho) flooded, causing thousands of drownings and ruined crops. According to government reports, more than 40 million hectares (almost 100 million acres) of agricultural land were rendered useless.

These floods were followed by a wave of further disasters: droughts, severe heat, more floods, typhoons, disease and insect infestations. In 1959, drought caused significant crop failures in Shaanxi, where output declined by more than 50 per cent, and Hubei, where it fell by 25 per cent.

The following year, Shanxi, Hebei, Shandong and Henan provinces suffered prolonged droughts, their production falling by more than half. China’s southern and coastal provinces also endured 11 major typhoons. In 1961, the northern provinces again suffered months of drought, while those in the south endured more flooding.

While these weather events are confirmed by independent meteorological data, their real impact on agricultural production is a matter of some debate. Most Western historians agree that failed government policies and human mismanagement were more culpable than natural disasters.

With the state commandeering such high levels of grain, communes were often left with insufficient food grain of their own. Some communes ignored the problem and maintained full rations, believing that things would improve or the government would send food relief. By the summer of 1959, however, food shortages had reached a critical point.

Relief should have come at the Lushan conference (August 1959), where the ambitious targets of the Great Leap Forward and the over-reporting of grain production were criticised by Peng Dehuai. Mao Zedong’s response was to attack his critics rather than relax his policies.

In the countryside, meanwhile, the peasants began to starve. Many sought alternative food sources like grass, sawdust, leather, even seeds sifted from animal manure. In Sichuan, thousands of peasants were forced to eat soil. Dogs, cats, rats, mice and insects were all eaten, dead or alive, until there were no more. One of the grisliest effects of the Great Famine was cannibalism.

The worsening situation meant that food supplies in the cities also dwindled, causing death rates in some urban centres to double; the government explained this as an effect of natural disasters.

The government suppressed information about the severity of the famine.

Nüshu: Female-only Language of China

China’s south-eastern Hunan province is a dramatic jigsaw puzzle of precipitous sandstone peaks, deeply incised river valleys and fog-shrouded rice paddy fields. Mountains cover more than 80% of the area, leaving many isolated hillside hamlets to develop independently of one another. It was here, hidden amongst the rocky slopes and rural river villages where Nüshu was born: the only writing system in the world created and used exclusively by women.

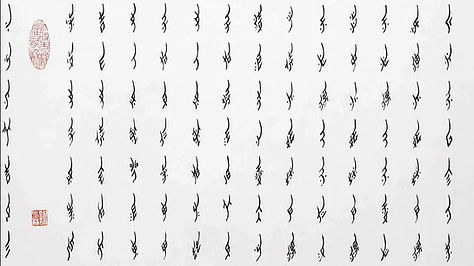

Meaning “women’s script” in Chinese, Nüshu rose to prominence in the 19th Century in Hunan’s Jiangyong County to give the ethnic Han, Yao and Miao women who live here a freedom of expression not often found in many communities of the time. Some experts believe the female-only language dates to the Song dynasty (960-1279) or even the Shang Dynasty more than 3,000 years ago. The script was passed down from peasant mothers to their daughters and practiced among sisters and friends in feudal-society China during a time when women, whose feet were often bound, were denied educational opportunities.

Many of these women were illiterate, and to learn Nüshu,

they would simply practise copying the script as they saw

it. Over time, Nüshu gave rise to a distinct female culture

that still exists today.

Remarkably, for hundreds or possibly even thousands of

years, this unspoken script remained unknown outside of

Jiangyong, and it was only learned of by the outside

world in the 1980s.

Though Nüshu is now understood as a means of communication for women who had not been afforded the privileges of reading and writing in Chinese, it was originally believed to be a code of defiance against the highly patriarchal society of the time. Historically, it was not socially acceptable for Chinese women to openly talk about personal regrets, the hardships of agricultural life or feelings of sadness and grief. Nüshu provided an outlet for the women and helped to create a bond of female friendship and support that was of great importance in a male-dominated society.

Women who created this strong bond were known as “sworn sisters” and were typically a group of three or four young, non-related women who would pledge friendship by writing letters and singing songs in Nüshu to each other. While being forced to remain subservient to the males in their families, the sworn sisters would find solace in each other’s company.

One of the most important uses of Nüshu came as a result of marriage. Traditionally, after a wedding, the bride would leave her parents’ home and move into the home of the groom. The bride would often feel isolated in her new role, so Nüshu provided a means for women to express sadness and lament broken friendships among one another.

The newlyweds’ move-in process would involve the handing over of a Sanzhaoshu or “Third-Day Book” that was made from cloth and given to the bride three days after her wedding. The mother of the bride and her close friends would express their feelings of sorrow and loss in the book while good wishes for future happiness would be recorded in the first few pages. The remaining pages would be left blank for future thoughts and to serve as a personal diary.

As part of the Revolution, China’s communist leaders were keen on eradicating the country’s feudal past and anyone found using Nüshu was denounced. And as women began to receive more formal education in the 1950s, the language further declined. Today, original Nüshu artefacts are rare, as many were destroyed during the Revolution.

In 2000, a Nüshu school opened in Puwei. Flanked by the Xiao river, there is an elegant Nüshu Garden and museum features a classroom and exhibition halls. Videos, paintings and cultural exhibits adorn the walls, while embroidery and calligraphy classes provide hands-on opportunities for cultural connection. The museum itself has recently been expanded and hosts an annual festival featuring poems and songs performed in Nüshu.

Nüshu, the women-only script of China, faced decline and near extinction, with texts burned or buried, because of several reaons.

Traditional Practices:

Nüshu writings were often seen as personal and intimate, and some women had their writings buried with them or burned as part of funerary rituals.

Cultural Revolution:

During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Nüshu was viewed as a "feudal" practice and was actively suppressed, with books and letters written in Nüshu burned, and research banned.

Decline of Nüshu:

The practice of Nüshu started to decline in the 20th century, as more women gained access to education and literacy in the standard Chinese script, and the communist revolution's focus on eradicating the country's feudal past also contributed to its decline.

Social and Political Changes:

The 1949 Chinese Revolution and subsequent socioeconomic reforms changed the state of society for women, which may have decreased the need for writing in a female-specific script.

Japanese Invasion:

During the Japanese invasion of China in the 1930s and 1940s, the script was suppressed by the Japanese because they feared that the Chinese could use it to send secret messages.

Visit the virtual Nüshu Museum!

Nüshu provided a way for women to cope with domestic and social hardships and helped to maintain bonds with friends in different villages. Convivial words of friendship and happiness were embroidered in Nüshu on handkerchiefs, headscarves, fans or cotton belts and exchanged. Though Nüshu wasn’t spoken, women at social gatherings sang and chanted songs or poems that varied from nursery rhymes to birthday tributes to personal regrets or marriage complaints using Nüshu phrases and expressions. Older women often composed autobiographical songs to tell their female friends about their miserable experiences or to promote morality and teach other women how to be good wives through chastity, piety and respect.

One-child Policy in China

China's one-child policy, implemented from 1979 to 2015, aimed to curb population growth by restricting most families to having only one child, though it was later relaxed to allow two and then three children.

A voluntary program was announced in late 1978 that encouraged families to have no more than two children, one child being preferable. In 1979 demand grew for making the limit one child per family. However, that stricter requirement was then applied unevenly across the country among the provinces, and by 1980 the central government sought to standardize the one-child policy nationwide. On September 25, 1980, a public letter—published by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party to the party membership—called upon all to adhere to the one-child policy, and that date has often been cited as the policy’s “official” start date.

The program was intended to be applied universally, although exceptions were made—e.g., parents within some ethnic minority groups or those whose firstborn was handicapped were allowed to have more than one child. It was implemented more effectively in urban environments, where much of the population consisted of small nuclear families who were more willing to comply with the policy, than in rural areas, with their traditional agrarian extended families that resisted the one-child restriction. In addition, enforcement of the policy was somewhat uneven over time, generally being strongest in cities and more lenient in the countryside.

Planned Economy: At the time, China had a planned economy, and population control was seen as a way to manage resources and facilitate economic growth.

Methods of enforcement included making various contraceptive methods widely available, offering financial incentives and preferential employment opportunities for those who complied, imposing sanctions (economic or otherwise) against those who violated the policy, and, at times (notably the early 1980s), invoking stronger measures such as forced abortions and sterilizations (the latter primarily of women).

The one-child policy produced consequences beyond the goal of reducing population growth. Most notably, the country’s overall sex ratio became skewed toward males—roughly between 3 and 4 percent more males than females. Traditionally, male children (especially firstborn) have been preferred—particularly in rural areas—as sons inherit the family name and property and are responsible for the care of elderly parents. When most families were restricted to one child, having a girl became highly undesirable, resulting in a rise in abortions of female fetuses (made possible after ultrasound sex determination became available), increases in the number of female children who were placed in orphanages or were abandoned, and even infanticide of baby girls. (An offshoot of the preference for male children was that tens of thousands of Chinese girls were adopted by families in the United States and other countries.) Over time, the gap widened between the number of males and females and, as those children came of age, it led to a situation in which there were fewer females available for marriage.

Another consequence of the policy was a growing proportion of elderly people, the result of the concurrent drop in children born and rise in longevity since 1980. That became a concern, as the great majority of senior citizens in China relied on their children for support after they retired, and there were fewer children to support them.

A third consequence was instances in which the births of subsequent children after the first went unreported or were hidden from authorities. Those children, most of whom were undocumented, faced hardships in obtaining education and employment. Although the number of such children is not known, estimates have ranged from the hundreds of thousands to several million.

The one-child policy was enforced for most Chinese into the 21st century, but in late 2015 Chinese officials announced that the program was ending. Beginning in early 2016, all families would be allowed to have two children, but that change did not lead to a sustained increase in birth rates. Couples hesitated to have a second child for reasons such as concerns about being able to afford another child, the lack of available childcare, and worries about how having another child would affect their careers, especially for mothers.

Religion and Superstitions of China

Let's start with the fact that Chinese didn't really have a word for "religion": the closest translation of the English word “religion” in Chinese is zongjiao, a term Chinese scholars adopted in the early 20th century when they were working with Western texts and needed to translate “religion.” To this day, zongjiao refers primarily to organized forms of religion, particularly those with professional clergy and institutional or governmental oversight. Zongjiao does not typically refer to diffuse religious beliefs and practices, which many Chinese people consider to be matters of custom (xisu 习俗) or superstition (mixin 迷信) instead.

Moreover, many Chinese people’s understanding of zongjiao may be influenced by the government’s view that religion reflects a backward mindset incompatible with socialism. In state media, for example, the term zongjiao is used alongside superstition to indicate corruption and wavering loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party.

But there is another reason why it is hard to pin down the number of people in China who are religious. It is a conceptual problem: Western definitions of religion and measures of religious participation – such as attendance at congregational worship services – fit the monotheistic religions of Christianity, Islam and Judaism but are less suited to traditional beliefs and practices in East Asia.

China’s relationship with religion has shifted throughout its modern history. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), religions were essentially banned, and followers were forced underground or persecuted as part of a campaign to eliminate “old” customs and ideas. In the 1980s, the CCP acknowledged the Chinese people’s complex relationship with religion. The following decades saw a revival of religious institutions and groups, and even tolerance of underground religions not directly under state control. Although Article 36 of the Chinese constitution says that citizens “enjoy freedom of religious belief” and bans discrimination based on religion, the law regulates religion by forbidding state organs, public organizations, or individuals from compelling citizens to believe in—or not believe in—any particular faith. Minors are also forbidden from entering places of worship. The Chinese Communist Party’s nearly 100 million members are required to be atheist.

The state recognizes five religions: Buddhism, Catholicism, Daoism, Islam, and Protestantism. The practice of any other faith is formally prohibited, although often tolerated, especially in the case of traditional Chinese beliefs. Religious organizations must register with one of five state-sanctioned patriotic religious associations, which are supervised by the United Front Work Department, a branch of the Communist Party.

The government’s tally of registered religious believers is around two hundred million, or less than 10 percent of the population. However, the number of Chinese adults who practice religion or hold religious belief is likely much higher because many believers do not follow organized religion and are said to practice traditional folk religion.

Under Xi, the CCP has pushed to sinicize religion, or shape all religions to conform to the doctrines of the Communist Party and the customs of the majority Han Chinese population. New regulations that went into effect in early 2020 require religious groups to accept and spread CCP ideology and values. Faith organizations must now get approval from the government’s religious affairs office before conducting any activities. The next year, the CCP banned unregistered domestic religious groups from sharing religious content online and prohibited overseas organizations from operating online religious services in China without a permit, particularly targeting Christianity-related content on the messaging service WeChat.

China has the world’s largest Buddhist population—an estimate of 4 percent to 33 percent of the country’s population (42 million to 362 million people) depending on how religious practices are measured. Though Buddhism originated in India, it has a long history and tradition in China and today is the country’s largest institutionalized religion. Chinese folk religions, in contrast, have no rigid organizational structure, blend practices from Buddhism and Daoism, and are manifest in the worship of ancestors, spirits, or other local deities.

In China, as well as in neighboring countries such as Japan and South Korea, there are many beliefs (such as in spirits) and practices (such as visiting shrines and making offerings to ancestors) that might be considered religious, broadly speaking.

In East Asia, the boundaries between philosophical, cultural and religious traditions – such as Buddhism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Taoism and folk religions with local deities and regional festivals – are often unclear. People may practice elements of multiple traditions without knowing or caring about the boundaries between those traditions, and often without considering themselves to have any formal religion.

Chinese culture is rich with superstitions, many tied to luck, fortune, and avoiding misfortune, particularly during events like Chinese New Year. Some common beliefs include avoiding certain colors, numbers, and actions, as well as specific food practices.

The Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution or The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was a decade-long period of political and social chaos caused by Mao Zedong’s bid to use the Chinese masses to reassert his control over the Communist party.

Its bewildering complexity and almost unfathomable brutality was such that to this day historians struggle to make sense of everything that occurred during the period.

However, Mao’s decision to launch the “revolution” in May 1966 is now widely interpreted as an attempt to destroy his enemies by unleashing the people on the party and urging them to purify its ranks.

In fact, the Cultural Revolution crippled the economy, ruined millions of lives and thrust China into 10 years of turmoil, bloodshed, hunger and stagnation.

Overall, Mao began to fear that the CCP was becoming too bureaucratic and that Party officials and planners were abandoning their commitment to the values of communism and revolution. Since the Great Leap Forward, he believed that he had been losing influence among his revolutionary comrades, and thus, the battle for China’s soul.

Mao started to worry that local party officials were taking advantage of their positions to benefit themselves. Rather than resolving such cases internally to preserve the prestige of the CCP, Mao favored open criticism and the involvement of the people to expose and punish the members of the ruling class who disagreed with him; he framed this as a genuine socialist campaign involving the central struggle of the proletariat versus the bourgeoisie.

Beginning in May 1966, Jiang Qing’s allies purged key figures in the cultural bureaucracy and criticized writers of articles seen as critical of Mao.

That same month, the top party official in Beijing University’s Philosophy Department wrote a big character poster, or dazibao, attacking the administration of her university. Faculty at the country’s other universities soon began to do the same, and radicals among faculty and students began to criticize Party members. This wave of criticisms spread swiftly to high schools in Beijing. Radical members of the leadership, such as Jiang Qing, distributed armbands to squads of students and declared them to be “‘Red Guards—the front line of the new revolutionary upheaval.”

Most historians agree the Cultural Revolution began in mid-May 1966 when party chiefs in Beijing issued a document known as the “May 16 Notification”. It warned that the party had been infiltrated by counter-revolutionary “revisionists” who were plotting to create a “dictatorship of the bourgeoisie”.

A fortnight later, on 1 June, the party’s official mouthpiece newspaper urged the masses to “clear away the evil habits of the old society” by launching an all-out assault on “monsters and demons”.

Chinese students sprung into action, setting up Red Guard divisions in classrooms and campuses across the country. By August 1966 - so-called Red August - the mayhem was in full swing as Mao’s allies urged Red Guards to destroy the “four olds” - old ideas, old customs, old habits and old culture.

Schools and universities were closed and churches, shrines, libraries, shops and private homes ransacked or destroyed as the assault on “feudal” traditions began.

Gangs of teenagers in red armbands and military fatigues

roamed the streets of cities such as Beijing and Shanghai

setting upon those with “bourgeois” clothes or reactionary

haircuts. “Imperialist” street signs were torn down.

Party officials, teachers and intellectuals also found

themselves in the cross-hairs: they were publicly humiliated,

beaten and in some cases murdered or driven to suicide after vicious “struggle sessions”. Blood flowed as Mao ordered security forces not to interfere in the Red Guards’ work. Nearly 1,800 people lost their lives in Beijing in August and September 1966 alone.

Nobody wanted to be considered a “reactionary,” but in the absence of official guidelines for identifying “true Communists,” everyone became a target of abuse. People tried to protect themselves by attacking friends and even their own families. The result was a bewildering series of attacks and counterattacks, factional fighting, unpredictable violence, and the breakdown of authority throughout China.

Some believe that this chaotic, violent response stemmed from the two decades of repression that the Party had imposed on China. Two particularly effective methods by which the CCP controlled the Chinese population were assigning class labels to each person, and giving the boss of each work unit nearly unlimited control over and knowledge of the lives of all the workers accountable to him or her. As a result, freedom of expression was denied, people were totally dependent on their bosses and were obliged to sacrifice and remain completely obedient to the Chinese nation, and only Party members exercised direct influence over their own lives. Thus, to the youth of the day, the Cultural Revolution represented a release from all their shackles, frustrations, and feelings of powerlessness. It also gave them the freedom to enact revenge on those whom they believed exercised undue influence over them or whom they had been told were “class enemies.”

Having any foreign ties—even having relatives living abroad—could easily lead to accusations of being a spy. Many innocent people wrongly accused of being spies were brutally persecuted or killed as “class enemies” in the numerous political movements throughout the 1950s and ’60s, especially during the Cultural Revolution.

After the initial explosion of student-led “red terror”, the chaos spread rapidly. Workers joined the fray and China was plunged into what historians describe as a state of virtual civil war, with rival factions battling it out in cities across the country.

The chaos and violence increased in the autumn and winter of 1966, as schools and universities closed so that students could dedicate themselves to “revolutionary struggle.” They were encouraged to destroy the “Four Olds”—old customs, old habits, old culture, and old thinking—and in the process damaged many of China’s temples, valuable works of art, and buildings. They also began to verbally and physically attack authority figures in society, including their teachers, school administrators, Communist Party members, neighbors, and even their friends, relatives, and parents. At the same time, purges were carried out in the high ranks of the Communist Party.

On New Year’s Day 1967, many newspapers urged coalitions of workers and peasants to overthrow the entire class of decision-makers in the country. The Red Guards were instructed to treat the Cultural Revolution as a class struggle, in which “everything which does not fit the socialist system and proletarian dictatorship should be attacked.”

Radical revolutionary groups responded with fervor, attempting to gain control over local organizations. However, the end result was that local authorities and Party leaders were now dragged into the fighting that was quickly enveloping the rest of society. In the absence of coordination, rival “revolutionary units” fought Party leaders and each other, and the unending series of local power struggles multiplied even further.

At this point, most party leaders, including Zhou Enlai, Mao Zedong, Lin Biao, and Jiang Qing, agreed that the disorder was becoming too widespread to control and the country was in serious danger of falling into anarchy. They began to emphasize studying Mao’s works rather than attacking class enemies, used workers’ groups to control student groups, and generally championed the PLA while denouncing “ultra-left tendencies.” Nevertheless, armed clashes continued until the summer of 1968, when Mao called on troops to quell an uprising at Qinghua University in Beijing. Five people were killed and 149 wounded in the confrontation, including workers who were shot by students. After this final gasp of violence, a semblance of order returned to the country: “Revolutionary Committees” consisting of representatives from the PLA, “the masses,” and “correct” Communist Party cadres were established to decide on leadership positions and restore order.

By late 1968 Mao realised his revolution had spiralled out of control. In a bid to rein in the violence he issued instructions to send millions of urban youth down to the countryside for “re-education”.

Overall, the Red Guards and other groups of workers and peasants terrorized millions of Chinese during the 1966–1968 period. Intellectuals were beaten, committed suicide, or died of their injuries or privation. Thousands were imprisoned, and millions sent to work in the countryside to “reeducate” themselves by laboring among the peasants.

He also ordered the army to restore order, effectively transforming China into a military dictatorship, which lasted until about 1971. As the army fought to bring the situation under control, the death toll soared.

The Cultural Revolution’s official handbook was the Little Red Book, a pocket-sized collection of quotations from Mao that offered a design for Red Guard life.

“Be resolute, fear no sacrifice, and surmount every difficulty to win victory!” read one famous counsel.

At the height of the Cultural Revolution, Little Red Book reading sessions were held on public buses and even in the skies above China, as air hostesses preached Mao’s words of wisdom to their passengers. During the 1960s, the Little Red Book is said to have been the most printed book on earth, with more than a billion copies printed.

The Cultural Revolution officially came to an end when Mao died on 9 September 1976 at the age of 82.

Mao had hoped his revolutionary movement would turn China into a beacon of communism. But 50 years on many believe it had the opposite effect, paving the way for China’s embrace of capitalism in the 1980s and its subsequent economic boom.

Although the Cultural Revolution largely bypassed the vast majority of the people who lived in rural areas, it had serious consequences for China as a whole. In the short run, of course, the political instability and the constant shifts in economic policy produced slower economic growth and a decline in the capacity of the government to deliver goods and services. Officials at all levels of the political system learned that future shifts in policy would jeopardize those who had aggressively implemented previous policy. The result was bureaucratic timidity. In addition, with the death of Mao and the end of the Cultural Revolution (the Cultural Revolution was officially ended by the Eleventh Party Congress in August 1977, but it in fact concluded with Mao’s death and the purge of the Gang of Four in the fall of 1976), nearly three million party members and countless wrongfully purged citizens awaited reinstatement. Bold measures were taken in the late 1970s to confront these immediate problems, but the Cultural Revolution left a legacy that continued to trouble China.

There existed, for example, a severe generation gap; individuals who experienced the Cultural Revolution while in their teens and early twenties were denied an education and taught to redress grievances by taking to the streets. Post-Cultural Revolution policies—which stressed education and initiative over radical revolutionary fervour—left little room for these millions of people to have productive careers. Indeed, the fundamental damage to all aspects of the educational system itself took several decades to repair.

Another serious problem was the corruption within the party and government. Both the fears engendered by the Cultural Revolution and the scarcity of goods that accompanied it forced people to fall back on traditional personal relationships and on bribery and other forms of persuasion to accomplish their goals.

Public Shaming

Public Shaming

Feminism in China

Feminism was one of the many ideologies that educated Chinese have embraced in their pursuit of modernity and rejection of an ancient dynastic system underpinned by a hierarchical sex-gender system that held chastity as the supreme value of women in the interest of patrilineal kinship. Just as the imagination of a modern China has never been singular, feminism has also been understood in diverse ways that, nevertheless, express a shared concern with gendered social arrangements.

At the turn of the twentieth century, anarchist, socialist, liberal, evolutionary, eugenic, and nationalist positions shaped various feminist articulations. In their proposals for changing gender hierarchy, rooted in ancient Chinese philosophy and gender norms based on Confucian ideals of gender differentiation and segregation, feminists expressed different imaginings of a better future: a more humane society that centered on social justice and equality, a modern society that allowed individuals to break away from the constraints of Confucian social

norms embedded in kinship relations as well as the control of an imperial polity, and a stronger nation that turned China from being the prey of imperialist powers into a sovereign state.

The May Fourth Feminist movement was the first feminist movement in China that challenged the gender stratification of Chinese society in an open and systematic fashion. This movement, however, included and was affected by only a small number of urban and elite women. The vast majority of women who lived in the countryside were only impacted minimally by this movement. It was after the Chinese Communist Revolution of 1949 that dramatic changes took place that had a strong impact on the lives of hundreds of millions of Chinese women and men. The new government of the People’s Republic made a firm commitment to guarantee the equality between women and men. The famous quotation by Mao Zedong reflects the determination by the government to raise women’s status: “Women hold up half the sky.” The basic law implemented when the People’s Republic of China was first established in 1949 stated: "The People’s Republic of China shall abolish the feudal system which holds women in bondage. Women shall enjoy equal rights with men in political, economic, cultural, educational and social life. Freedom of marriage for men and women shall be put into effect" (Article 6).

The dramatic changes in China since the Cultural Revolution have had a mixed and inconsistent impact on women’s movement and status in China. On the one hand, the literature shows that Chinese women experienced rapid progress in terms of gender equality during the Cultural Revolution. Women’s labor force participation rate, as has been discussed earlier, remained high, and women’s representation in higher educational institutions was also higher during the Cultural Revolution, compared with either earlier or later times. On the other hand, however, there is evidence that women still suffered an extremely low status in Chinese culture. Repeated reports of female infanticide after the implementation of the one-child policy was one of the first messages that alarmed the

Chinese as well as the world population as an indicator of the persistence of women’s low status in China. It was during the Cultural Revolution that the All Women’s Federation was forced to suspend itself, an indicator that women’s affairs were placed in a secondary position compared with what the Chinese Party considered as the more pressing political agenda during those years. The ultra-leftist Cultural Revolution Movement that lasted for 10 years completely ignored women’s issues and women were either hardly differentiated from men, or they were simply rendered masculine. The uniform color and style of the popular outfit for both women and men during the Cultural Revolution, and slogans such as “Whatever men can do, women can do too,” using men as the yardstick to evaluate women, attest to this argument.

After the “Reform and Opening Up” in 1978, Western feminist theories began to enter China, and some Chinese universities started offering Women’s Studies courses. In 1995, China hosted the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, which not only facilitated more cultural exchange between Chinese and international feminist scholars and activists but also introduced the concept of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to China. After that, feminist NGOs began to spring up across the country.

Ancient China experienced a long period of patriarchal society, emphasizing "Ignorance is a woman's virtue", when women basically did not receive education, thus most are illiterate. In the 19th century when links between East and West increased and more women were educated in schools or missionary girls' schools. It was not until the 20th century that girls' schools were established, mainly in Jiangsu, Shanghai and other economically, culturally and transportation-developed areas, but the number of schools was still not large. After the 1911 Revolution, women's education had great progress due to the legal confirmation of women's right to education and the progress of social concepts, as well as the strong demand of women's right on equal education. During that period, social unrest and unbalanced development impeded the development of women's education. By 1949, the female illiteracy rate was as high as 90%. Since the founding of new China, women's education has been on the right track and developed rapidly. In particular, over the past 40 years of reform and development, women's education has been fully developed, especially in higher education.

On July 27, 1995, prior to the Fourth World Conference on Women, the State Council published the Program for the Development of Chinese Women, the first official guideline of its kind in China. The preamble of the program states, ‘Women are a great force for human civilization and social progress, and therefore their development is a major indicator and gauge of social development and progress. It should be the common task of governments at all levels, competent authorities, social groups and all the people to promote the progress and development of women’.

At the Fourth World Conference on Women, China solemnly declared to the world, ‘We are committed to the development and progress of women, and have made gender equality a basic national policy for advancing social progress’. This declaration, credited as a major contribution to promoting women’s development, caused a sensation in the international community and won widespread support. More important, a Chinese version of gender equality gradually emerged through the elevation of the issue to national policy. It consisted of five major elements:

-

gender equality must be based on a recognition of differences between the sexes;

-

protection of women’s right to all-round development must be made a focus;

-

policy making should be geared towards the protection of women, with full consideration to the development needs of women in different regions and classes;

-

women’s role in socioeconomic development must be valued, and their talent and creativity must be fully unleashed in China’s socialist construction; and

-

gender equality must be realized by encouraging women to work and coordinate with men, and women’s development and gender equality must take place in the context of coordinated social development.

It was the Fourth World Conference on Women that marked a new beginning for the women’s movement in China. It led to the legalization of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), spread such notions as equality between the sexes, women’s empowerment, and gender among a Chinese audience, and for the first time included women’s rights within human rights, which would provide Chinese feminists with new resources in their discourse and fresh impetus in their campaign to eliminate social mechanisms that would spawn gender inequality in the late 1990s.

China in 1990s

Postsocialist China (1989- )

Following the violent suppression of protests at the end of the 1980s, the Chinese government, led by Deng Xiaoping, faces a crisis and questions about how to proceed with economic reforms. Deng, over the opposition of more conservative communist voices, doubles down on economic growth in southern China. A period of tremendous growth follows, though increased prosperity also opens profound wealth gaps and relies on the exploitation of labor. China’s southern, coastal provinces become the “Factory of the World.” Workers migrate from rural areas to Chinese cities, reversing the nation’s urban/rural demographics, with about 2/3 of China’s population living in cities in 2022.

Rice Plowing

Some visual footage on plowing the rice fields by hand.

Hand plows

See the video from 00:00 till 05:00

See the video from 01:31 till 03:13

Rural vs Urban

After its introduction in 1979, the controversial One Child Policy, which promoted late marriage and delayed child bearing and limited the number of children born in rural families to 1.5 (two for a first-born girl, otherwise one), was firmly implemented and shifted the vast rural China household structure — and thus, agricultural workforce — dramatically to fewer children. Then in the mid-1980s, the Hukou System — a residence registration system devised in the 1950s to record and control internal migration and which ultimately hindered rural-to-urban movements — began to loosen in response to the demands of both the market and rural residents wishing to seek greater economic opportunity in cities. China's rural-to-urban population movement is largely viewed as a response to the economic reform, and better employment opportunities in destination cities have generally been the main determinant in the decision to migrate.

While treaty ports along China's coast were feeling the direct impact of foreign demands during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most people in China were — and still are — rural people, living in towns and villages. Although most farmers in China owned some land and often had sources of income apart from farm work, such as handicrafts, life was generally harsh. Farm plots were very small, averaging less than two acres per family, and peasants had little access to new technology, capital, or cheap transport.

Traditional Marxist thinking relegated peasants to a class which Marx believed represented "barbarism within civilization" — people who were unable to develop revolutionary consciousness and only wanted land and bread (food). In the 1920s, Chinese leftists began to change their view of the revolutionary potential of the rural population. Some, like the Guomindang organizer in South China, Peng Pai, had great success from 1921-23 in convincing disaffected farmers to form peasant associations and challenge oppressive landlords. Likewise, Mao Zedong's own work in the rural areas in 1925 and 1926 led him to see the farmers differently. When Nationalists forces after 1927 drove him and other Communists to rural hideouts from their urban bases, they intensified their work among the rural population. Their belief in rural revolution thus became a hallmark of Chinese Communist thinking.

The death of Mao and the official end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976 led to a change in policy direction and an embrace of market reforms. By 1983, most communes had been dismantled and agricultural land nationwide was reorganised, with production rights redistributed to individual households—known as the household responsibility system. As the 1980s progressed, national policymakers’ attention shifted from the countryside to urban growth.

This narrative of the peasant as historical relic and developmental obstacle fit well into what was now an era of worldwide hegemonic neoliberalism characterised by widespread processes of peasant dispossession across the Global South. It was also highly compatible ideologically with the new form of land-based capital accumulation that was emerging in China. Fiscal reforms in 1994 had reorganised national budgetary allocations so that local governments further down in the bureaucratic hierarchy could no longer rely on distributions coming from higher up, but instead had to fend for themselves. The consequences for China’s countryside were profound. Cash-strapped local governments layered extra taxes and fees on to rural households and, in addition, turned systematically to processes of converting collective rural land to state-owned urban land that could then be leased to developers for revenue. Processes of rural to urban migration—already under way as China opened to foreign investment and national policymakers embraced China’s new identity as ‘factory of the world’—accelerated. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 exacerbated these processes. As numbers of rural–urban migrant workers soared to world historic levels, conditions in the countryside deteriorated. City government officials had by now become accustomed to turning a blind eye to the still existing hukou, welcoming the supply of cheap labour that appealed to outside investors. Rural migrants in cities were typically treated as second-class citizens, however, lacking access to the city’s resources and barred from settling there permanently.

Expanding income disparities and social inequality among different classes, groups and regions have been emerging as prominent issues in contemporary China. The gaps began to widen when China embarked on the path of reform and opening to the outside world three decades ago.

Before the 1980s, and more specifically, during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), “the advantage of coming from an educated family or an intelligentsia or cadre family was drastically reduced” and the “weak association between father’s socio-economic status and son’s educational attainment” reflected “massive state intervention.” But the distribution became more and more unequal after 1980, and especially after 1990. And the increase in educational opportunities since the mid-1990s has not translated into a more equal distribution of educational resources: rather the opposite has occurred.

Concerning the income gap, by 1999, urban women’s income had dropped to 70.1 percent of their male counterparts, down from 77.5 percent in 1990. Rural women’s income was only 59.6 percent that of men’s, 19.4 percentage points less than in 1990.

The Great Leap Forward

Great Leap Forward, in Chinese history, the campaign led by the Chinese Communist Party between 1958 and early 1960 to organize China’s vast population, especially in large-scale rural communes, to meet the country’s industrial and agricultural problems. The Chinese hoped to develop labor-intensive methods of industrialization, which would emphasize manpower rather than machines and capital expenditure. Thereby, it was hoped, the country could bypass the slow, more typical process of industrialization through gradual accumulation of capital and purchase of heavy machinery. The Great Leap Forward approach was epitomized by the development of small backyard steel furnaces in every village and urban neighborhood, which were intended to accelerate the industrialization process.

Great Leap Forward era propaganda poster. The Chinese text above this propaganda poster reads, “Take the road to cooperation.”

The promulgation of the Great Leap Forward was the result of the failure of the Soviet model of industrialization in China. The Soviet model, which emphasized the conversion of capital gained from the sale of agricultural products into heavy machinery, was inapplicable in China because, unlike the Soviet Union, China had a very dense population and no large agricultural surplus with which to accumulate capital. After intense debate it was decided that agriculture and industry could be developed at the same time by changing people’s working habits and relying on labor rather than machine-centered industrial processes. An experimental commune was established in the north-central province of Henan early in 1958, and the system soon spread throughout the country.

Under the commune system, agricultural and political decisions were decentralized, and leadership roles were often assigned based on communist ideological purity rather than practical expertise. The peasants were organized into brigade teams, and communal kitchens were established so that women could be reassigned from domestic work. The program was implemented with such haste by overzealous cadres that farming tools were often melted in the backyard furnaces to make steel, and many farm animals were slaughtered by discontented peasants. These errors in execution were made worse by a series of natural disasters and the withdrawal of Soviet support.

Photo of Chinese workers with propaganda song beneath. Worker songs, like the one beneath this photo, were written and circulated during the Great Leap Forward as a form of Communist propaganda.

The inefficiency of the communes and the large-scale diversion of farm labor into small-scale industry seriously disrupted China’s agriculture, and three consecutive years of natural calamities helped to turn the disruption into a national disaster; in all, about 20 million people were estimated to have died of starvation between 1959 and 1962 (see The Great Chinese Famine tab).

This breakdown of the Chinese economy caused the government to begin to repeal the Great Leap Forward program by early 1960. Private plots and agricultural implements were returned to the peasants, expertise regained its primacy over ideology, and the communal system was broken up. The failure of the Great Leap produced a division among the party leaders. One group blamed the failure of the Great Leap on bureaucrats who the group felt had been overzealous in implementing its policies. Another faction in the party took the failure of the Great Leap as proof that China must rely more on expertise and material incentives in developing the economy. Some concluded that it was against the latter faction that Mao Zedong launched his Cultural Revolution in early 1966 (see the Cultural Revolution tab).

Left-behind Children in China

One consequence of China’s mass rural-to-urban migration since the 1980s is an increase in family separation and a rise in left-behind children. The term refers to children younger than 18 years old who remain with either one parent or, where both parents migrate, other caregivers. While statistics vary, the most recent estimate, from 2020, suggests there are more than 60 million left-behind children, mostly residing in rural areas.

Research since the 1990s reveals two distinct generations of left-behind children. The first generation consisted of children born in the 1980s and 1990s. During this period most rural migrants were male, and both migration distances and duration were relatively short. In addition, parents typically did not leave the village until their children were at school. The second generation are children born after 2000. Since then, more women, including mothers, have migrated out of the villages, and migration distances and the duration has also been longer than with the parents of the first generation. As a result, more left-behind children are being raised by grandparents or other relatives. In addition, parents are separating from their children at an earlier age. For instance, the percentage of zero-to-two-year-olds who remain in a village without their parents has sharply increased from the first to second generation.

in the 1980s and 1990s, both parents tend to be at home for the first year or two of a child’s life, and it was typically fathers who left the village for work. In addition, those who left tended to seek off-farm employment closer to home. This was due to the strict hukou (household registration) system that limited migration to cities, as well as the country’s greater reliance on agriculture.

Parental absence at an earlier age can have an adverse effect on early childhood development. Studies find that the absence of the mother in particular has a negative effect on the cognitive development and nutrition of rural children younger than two. Rural children have delayed development outcomes compared to their urban counterparts, but it is more pronounced when mothers separate from their children within their first two years. Many studies find that parental migration has a significantly negative impact on the children’s education, resulting in lower test scores, worse school enrollment and fewer years of schooling overall. Children’s middle-school academic performance improves when migrant parents return home.

The first generation of left-behind children typically stayed with their mother and grandparents. The women who remained in the village looked after the children as well as grandparents, the house and the farmland. During this period, almost every village had an elementary school, and there was a middle school in a nearby town or county. As more rural women entered the urban workforce, more fathers stayed behind, caring for both children and grandparents.

Since the inception of the hukou system in 1958, rural people living in cities have faced institutional discrimination in areas including employment, access to public education, health care and housing. The hukou reform that began in the early 2000s has had a significant influence on migrant parents and their children, offering increasing access to public education.

Another way municipal governments control migration and education is through home ownership. High school education in China is not compulsory, and to enroll, students must take an entrance exam. To qualify for the exam, there is an official registration process that may require an urban hukou as well as proof of their parents’ home ownership. Many migrant parents have therefore left younger children behind in rural areas until they can afford to purchase an urban apartment to meet such requirements. Even then, it is challenging for migrant students to compete for a limited number of places with urban peers who have enjoyed better primary and secondary education and then, if accepted into an urban high school, to keep up with their classmates.

Feminism in the US in 1990s

As the third wave started in the 1990s, women’s rights activists longed for a movement that continued the work of their predecessors while addressing their current struggles. In addition, these women wanted to create a mainstream movement that was inclusive of the various challenges women from different races, classes, and gender identities were facing. Image: (L-R) Second Wave feminist Bella Abzug with law professor Anita Hill.

Although it is difficult to isolate the single incident that started the third wave, there are two events that are traditionally credited with inspiring a new generation of women’s rights activists. The first one was the 1991 Anita Hill hearings that sparked national feminist support when Hill testified against a Supreme Court nominee for sexual harassment. While watching the hearings, Rebecca Walker, daughter of second wave icon Alice Walker, began describing the political climate as ”The Third Wave.”

In addition, beginning in the 1990s, underground feminist punk rock bands surfaced in “Riot Grrrl” groups. These “girrl” groups combined punk culture with politics, feminism, and style. Both of these occurrences helped to usher the feminist movement into a new era of women’s activism.

Right at the beginning of the third wave, feminist scholars started to publish new literature that helped readers better understand feminist theory. In 1989, lawyer and theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw developed “intersectionality” to show how someone’s various identities (race, class, gender, etc.) overlap to influence how they are treated. This theory led to “intersectional feminism,” that formed as a response to the multiple ways women are oppressed. In 1990, two other revolutionary scholars incorporated the idea of intersectionality into their work. Judith Butler’s “Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity” and Patricia Hill Collins’ “Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment” both approach feminist theory by studying women’s social and political identities.

On October 11, 1991, the world watched as attorney Anita Hill testified against U.S. Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas for sexual harassment. In the televised hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Hill declared that Thomas had repeatedly harassed her while she was his employee at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. According to Hill, when she worked as his aide, Thomas frequently pressured her to go on dates and often made sexually inappropriate comments during their work conversations. Despite Hill’s testimony, Thomas was still confirmed as a Supreme Court Justice after the three-day hearings.

Although both Thomas and Hill were African American, Thomas believed that the hearing against him was equivalent to a “high tech lynching.” This metaphor suggested that he was being persecuted because of his race. As they both testified before an all-white, all male committee, the history of African American women also being lynched and persecuted was not discussed. Lawyer and author of the ”intersectionality” theory Kimberlé Crenshaw was a member of Hill’s legal team. She later wrote that the belief that lynching was the ultimate symbol of racist terror “erased black women from the picture.” In addition, one of the most prominent historical figures against the lynching of African Americans was a black woman.

After the hearings, African American feminists and historians across the United States came together and collectively raised $50,000 to purchase a full-page ad in the New York Times. Their manifesto entitled, “African American Women in Defense of Ourselves,” was signed by 1,600 women including black feminist historians Barbara Ransby, Deborah King and Elsa Barkley Brown. These women fought against the treatment of Hill during the hearings and stated; “We are particularly outraged by the racist and sexist treatment of Professor Anita Hill, an African American woman who was maligned and castigated for daring to speak publicly of her own experience of sexual abuse.” Following Hill’s story, many other women had the courage to speak out against their own experiences with sexual misconduct.

For many mainstream feminists, the Hill case marked a turning point in women’s activism. Not only were women speaking publicly about sexual assault, but the visibility of the case also caused women to question the male-dominated leadership in Congress. Before the hearings, seven democratic women from the House of Representatives marched over to the Senate to demand a further investigation of the accusations against Thomas. Although he was still confirmed as a justice, feminists began to push for a more active role in political leadership. The very next year, more women were elected to Congress on voting day than in any previous decade. That year became known as “The Year of the Woman,” and 27 women were elected to Congress.

One of the early women’s groups that contributed to the success of The Year of the Woman was “EMILY's List.” This women’s political network provided the fundraising and resources necessary for an endorsed candidate to successfully run for political office. These women used the strategy of raising money early in a candidate’s campaign so it would attract more donors. This principle was the foundation of the organization’s name “EMILY's List” that is an acronym for "Early Money Is Like Yeast,” because yeast “makes the dough rise.” EMILY's List continues to endorse pro-choice Democratic women running for office to this day.

In addition to political affinity groups, punk rock musicians also began to emerge with distinctly feminist agendas. Responding to various forms of sexism, feminist musicians decided to organize a “girl riot” through their activism. These women started their own bands and created their own publications dedicated to women’s empowerment. Much of their content addressed issues including; sexism, patriarchy, abuse, racism, sexuality and rape. Popular bands such as Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy, all lead this trend of activism.

Prior to the evolution of the Riot Grrrl Movement, the Guerrilla Girls set the foundation for radical feminist revolt. They formed in 1985 in response to sexism and racism in the art world. This anonymous group of feminist artists from New York City decided to take the feminist art movement one step further by intentionally disrupting the status quo. These women created posters, billboards, and made public appearances in gorilla masks to reveal the sexist and racist practices in the creation and study of visual art. One of their most famous posters was an image of a naked woman in a gorilla mask next to the phrase “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” The poster also provides the statistics that show the low number of women featured in the Modern Art sections, compared to the high percentage of nude art that features women.

Starting in the early 1990s, radical feminist art seeped into the music world as women affiliated with the Riot Grrrl feminist movement emerged in Olympia, Washington. One of the frontrunners of this movement was Kathleen Hanna, the lead singer of the feminist band Bikini Kill. After collaborating with other Riot Grrrl artists on a small magazine called “Riot Grrrl,” The Bikini Kill Zine (fanzine) was created. These “zines” used punk rock culture to address feminist issues. By 1991, the Bikini Kill Zine published the Riot Grrrl Manifesto that clearly outlined the reasons for this recent surge of feminist activism through music.

Statements from The Riot Grrrl Manifesto, published in 1991 in the Bikini Kill Zine 2:

BECAUSE us girls crave records and books and fanzines that speak to US that WE feel included in and can understand in our own ways.

BECAUSE we wanna make it easier for girls to see/hear each other's work so that we can share strategies and criticize-applaud each other.

BECAUSE we don't wanna assimilate to someone else's (boy) standards of what is or isn’t.

BECAUSE we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak.

Many women flocked to these punk rock groups that valued self expression and collective revolt. Kathleen Hanna was known for empowering women at her concerts by shouting “Revolution Girl Style Now!” or “Girls to the front!” to encourage her female attendees to come to the front of the audience. Not only did this provide a safe space for women at rock concerts, but this practice also became a symbol of the call for women to be brought to the forefront in all areas of life. As the movement grew, other Riot Grrrl bands developed across the country and established nationwide chapters. Many of these feminists played their music during pro-choice rallies and advocated for the reproductive rights of women.

By the mid-1990s, Riot Grrrl bands became so well-known that pop culture started to incorporate some of the movement’s terminology. The phrase “Girl Power,” was often used by Bikini Kill and could be found throughout the pages of Riot Grrrl zines. However, this phrase quickly became a pop culture slogan after girl groups like The Spice Girls started promoting a “girl power” theme. Due to the mixed messaging, mainstream media began to attach the political Riot Grrrl groups to pop culture bands that were not associated with the movement. Many Riot Grrrl groups spoke out against this media misrepresentation, but unfortunately it had already become a pop culture phenomenon. In response, several Riot Grrrl groups dissolved. However, many former participants continued to make political music. Even though Bikini Kill released their last album in 1996, lead singer Kathleen Hanna has continued to merge music and activism.

Although the prominence of Riot Grrrl groups was short lived, their specific brand of feminism resonated with many women that may not have identified with the concerns or practices of mainstream “cookie-cutter” feminism. These Riot Grrrl groups inspired radical global activism for decades to come, with Riot Grrrl bands and chapters forming in Asia, Europe, Australia, and Latin America well into the 2000s.

As third wave feminists transitioned into the 21st century, it was clear that there were several individualized goals of the movement. Women spoke out in various interest groups about everything including abortion, eating disorders, and sexual assault. However, the Anita Hill hearings and Riot Grrrl groups of the early 1990s were central to the development of this third wave. In 2003, Robin Morgan edited an updated version of her original feminist anthology written in 1970. Her new edition called, “Sisterhood Is Forever: The Women's Anthology for a New Millennium,” featured pieces by both Anita Hill (“The Nature of the Beast: Sexual Harassment”) and Kathleen Hanna of the Riot Grrrl movement (“Gen X Survivor: From Riot Grrrl Rock Star to Feminist Artist”). Some scholars believe that the third wave never came to an end and it continues on to this day. However for others, new technology and social campaigns have marked the beginning of a fourth wave of feminism.

Dogs in China

China's relationship with dogs is complex, and it has changed many times over that nation's long history. The archaeological evidence says that the early ancestors of modern Chinese were already keeping dogs during the Neolithic age, which is more than 7000 years ago. The evidence suggests that the dogs were being kept for three reasons, protection, hunting and food.

The protective function of dogs was an important one. It was not uncommon to have dogs tied up near the door of the house, or kept in the front yard, to sound the alarm if someone approached and to deter unwanted visitors from entering.

The use of dogs for hunting was quite common up until around the 10th century and then it declined as more of the prime hunting land was converted to agricultural use. By the time the Ming Dynasty arose in the 14th century, hunting had become mainly a leisure activity enjoyed by the nobility. Hunters often used a now-extinct breed of dog known as the xigou, which was related to the Saluki or to the long-haired Greyhound (which is now also extinct). They were used mainly to hunt rabbits and other small game.

It was at this same time that many wealthy Chinese started keeping dogs as house pets, and this is also when we see the first appearance of the Pekingese which ultimately became the favorite lapdogs among the members of the imperial court. Although dogs were being kept as pets they also doubled as rat catchers. Some were specifically selected for that job, thus the Chinese Crested was the preferred rat catcher that sailors kept on the ships of that time.

However, meat was a rare commodity in feudal China, which drove the Han Chinese in both the northern and southern provinces to eat dog meat. For farmers, this was a valuable supplement to their diets which consisted mainly of rice and vegetables.

Toward the end of the first century, the practice of eating dogs began to decline due to the spread of the newly introduced religions of Buddhism and Islam. In both of these religions, it is forbidden to eat certain animals, and this included dogs. These religions were more widely accepted among the upper classes, and it soon became a social taboo to eat dogs among the higher ranks of society. However in the general population, especially in rural areas, the practice continued.

The practice of keeping dogs as pets began to increase in popularity in China during the 20th century. Unfortunately, it met a major setback during the rule of Mao Zedong. In the mid-1960s Chairman Mao's Cultural Revolution banned pet dogs, claiming that they were consuming too much of the nation's limited food supplies and were symbols of Western capitalist elites. People who owned pet dogs were publicly shamed, dragged out into the street and forced to watch while their pet was beaten to death. With Mao's demise in 1976, The Cultural Revolution came to a fairly abrupt end and so did the negative consequences of keeping a dog.

In rural China, dogs are common for households and are generally used as the “gate watcher.” These dogs are usually chained for life on the family property, never allowed to go inside the house, sometimes not protected against the elements, and seldom treated with kindness.

With rapid urbanization over the last thirty years, millions of people left rural communities and moved into high-rise apartment buildings. Unfortunately, dogs were left behind because they are regarded as “too dirty” to live inside a home.

Buddhism in China

Buddhism (Fojiao 佛教) is the largest officially recognized religion in China. Buddhism in China has three main branches. Han Buddhism, or Chinese Buddhism, accounts for the vast majority of the country’s Buddhists, as measured by the number of registered temples. Tibetan Buddhism and Theravada Buddhism are practiced primarily by ethnic minorities in the Tibetan Plateau, Inner Mongolia and along the southern borders with Myanmar, also called Burma, and Laos. In China, the word “Buddhism” typically refers to Han Buddhism.

Although Buddhism originated in India, Han Buddhism has developed distinctly Chinese characteristics while also influencing older Chinese belief systems. Han Buddhists generally espouse the Confucian ideal of filial piety (xiao 孝) and have adopted practices that align with ancestor worship, such as praying for the well-being of deceased ancestors.45 They also have incorporated the Taoist practice of breathing exercises.

In the past decade, government policies have been relatively lenient toward Han Buddhism. President Xi Jinping has extolled (Han) Buddhism as one of the essential forms of Chinese traditional faith with a role to play in restoring morality, and has commended it for having “integrated … with the indigenous Confucianism and Taoism.”

As with Taoism and folk religion in China, assessing the size of the Buddhist population is challenging due to Buddhism’s blurry boundaries with other traditional Chinese religions. Unlike Christianity and Islam, Buddhism does not require exclusivity of belief or practice.